The nineteenth century saw a huge growth in the population of Great Britain.

The reason for this increase is not altogether clear. Various ideas have been put forward; larger families; immigration, especially large numbers of immigrants coming from Ireland fleeing the potato famine .

By the end of the century there were three times more people living in Great Britain than at the beginning.

Therefore all these factors – population explosion, immigration both foreign and domestic – added up and resulted in a scramble for any job available. If work dried up and men were laid off, they had no savings to fall back on.

Victorian society did not recognize that there was a lower class.

'The Poor' were invisible. Those members of England who worked as chimney sweeps, rat catchers, or spent their days in factories had no place in the echelon of the upper class, although their services would be needed from time to time.

Etiquette played little part in the poor's daily existence. But that's not to say that pride wasn't available. There was a 'social stigma' to applying for aid, and some families preferred to keep to themselves and figure out their own methods of survival.

This picture also expresses the ideal image of womanhood, although it depicts a lower-class family. It is obvious that this woman looking up at her husband in rapt admiration completely relies on his manly powers as the financial and mental supporter of the family. The simple, but clean and comfortable interior of their house and the neatly dressed child suggest that the woman is perfect enough to keep their house properly both as a wife and as a mother.

In Victorian England, a great stratification existed between the upper and lower classes. The upper classes claimed that the lower classes "cannot be associated in any regular way with industrial or family life," and that their "ultimate standard of life is almost savage, both in its simplicity and in its excesses." (Reader, Victorian England, 117-119, 1973)

A lack of adequate nutrition, medicinal care, and sanitary resources also contributed to the stigma attached to poor people. The disease and malnutrition that ran rampant among the poor caused 'stunted physiques" and pale countenances that caused not only economic division between the classes, but also physical division as well.

A ne'er-do-well exploits his gentle daughter's beauty for social advancement in this masterpiece of tragic fiction. Hardy's 1891 novel defied convention to focus on the rural lower class for a frank treatment of sexuality and religion. Then and now, his sympathetic portrait of a victim of Victorian hypocrisy offers compelling reading.

In the 19th century, children of the poor lived in very difficult circumstances, near factories and in unhealthy flats with no hygiene. The houses or tenements were cramped and a simple cold could often lead to death. Sanitation didn't exist until around 1900's. These conditions favoured infant mortality; and diseases like cholera flourished when they drank tainted water. The rate of mortality was high. There were no vaccines available in the 19th century.

In the 19th century, children of the poor lived in very difficult circumstances, near factories and in unhealthy flats with no hygiene. The houses or tenements were cramped and a simple cold could often lead to death. Sanitation didn't exist until around 1900's. These conditions favoured infant mortality; and diseases like cholera flourished when they drank tainted water. The rate of mortality was high. There were no vaccines available in the 19th century.

'Please, sir, I want some more.'

'Please, sir, I want some more.'

Nine-year-old Oliver is a resident in the parish workhouse where the boys are "issued three meals of thin gruel a day, with an onion twice a week, and half a roll on Sundays." The workhouse is run by Bumble the Beadle, Limbkins is Chairman of the Board of Guardians for the workhouse.

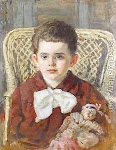

Children of the poorer families would probably have worn second hand clothes that were often patched to make them last longer.

Children of the poorer families would probably have worn second hand clothes that were often patched to make them last longer.

If they were lucky they might have had dolls made from rags, tin soldiers, wooden toys carved by family members.

If they were lucky they might have had dolls made from rags, tin soldiers, wooden toys carved by family members.

"Frozen Charlotte" All Bisque Victorian Penny Dolls

"Frozen Charlotte" All Bisque Victorian Penny Dolls

" Peg Dolls"

" Peg Dolls"

They played outside games when they had time that would cost very little - a hoop to run down the street with, hopscotch or maybe a game of marbles made from clay. You could make dibs from clay which would be shaped then be heated in the oven to make them hard.

They played outside games when they had time that would cost very little - a hoop to run down the street with, hopscotch or maybe a game of marbles made from clay. You could make dibs from clay which would be shaped then be heated in the oven to make them hard.

Child Labour

They often worked long hours in dangerous jobs and in difficult situations for a very little wage. At an early age the children would be out looking for work or roaming the streets looking for odd jobs. Some would be stealing for food.

They often worked long hours in dangerous jobs and in difficult situations for a very little wage. At an early age the children would be out looking for work or roaming the streets looking for odd jobs. Some would be stealing for food.

Pickpockets were in abundance and even a stolen handkerchief or scarf could be sold for food.

There were the climbing boys employed by the chimney sweeps.

There were the climbing boys employed by the chimney sweeps.

Little children were hired to scramble under machinery to retrieve cotton bobbins; boys and girls working down the coal mines, crawling through tunnels too narrow and low to take an adult.

Little children were hired to scramble under machinery to retrieve cotton bobbins; boys and girls working down the coal mines, crawling through tunnels too narrow and low to take an adult.

Some children worked as errand boys, crossing sweepers, shoe blacks, and they sold matches, flowers and other cheap goods.

Some children worked as errand boys, crossing sweepers, shoe blacks, and they sold matches, flowers and other cheap goods.

The best way for society to deal with the poor was to ignore them. They were 'burdens on the public'.

Although Poor Laws were put into place, it wasn't until after the Victorian age ended that 'the lower class' was able, through education, technology, and reform, to raise itself( in some cases literally,) out of the gutter.

Victorian society could be quite pleasant, but only depending on your financial status.

From an Article by "Tudor Rose"

By Edwardian times, old attitudes about the 'deserving poor' were beginning to change. The work of organizations like the Waifs and Strays' Society alerted people to the problems of destitute children, whose poverty was through no fault of their own.

.jpg)

.jpg)